by Andrew Hunter

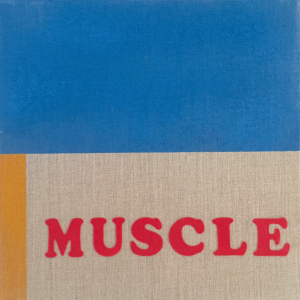

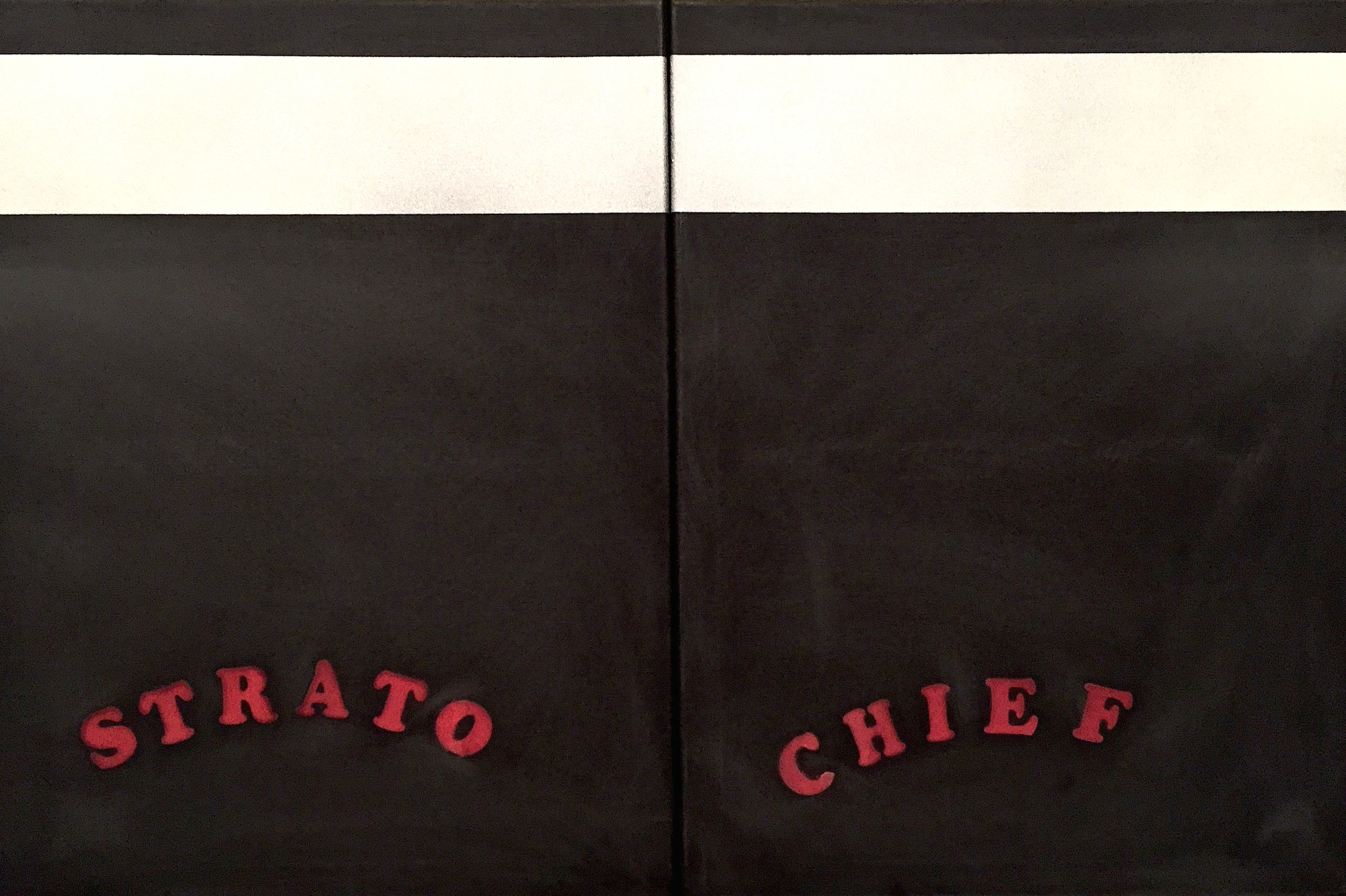

It is very difficult to write convincingly of painting, to write affected by painting as opposed to about it, which is to describe it. Painting can be explained, but do you get it? Here’s the dilemma. When I encounter the paintings of an artist like C.Wells I ask myself, “What is the code, the system that informs and defines the making of this work?” And then inevitably, and perhaps sadly, because of my “upbringing” at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design in 1980s, I ask the next question, “What is the artist’s position, the intent here; is this a pose, a theoretical exercise; is it insincere or authentic?” In short, “Are these paintings?” or, on the other hand, are they “painting as model,” to borrow a phrase from Yve-Alain Bois. 1So much of the painting witnessed in the past twenty years begs these questions. They are questions asked at the end of a powerful trajectory of Modern painting, primarily, but nor exclusively, American, that leads to the “endgame” imbedded in Benjamin Buchloh’s (mis)reading of Gerhard Richter’s” paintings or the work of Sherry Levine, for example, in the l980s. And here’s that trajectory in a nutshell: Marcel Duchamp’s Ready-mades (art as idea), Clement Greenberg’s painting as paint, Frank Stella’s stripes, Jasper Johns’ flags, Minimalism, Lawrence Weiner’s Conceptualism, all leading to the end of painting, painting as code, beyond the “yellow brick road” where the painter as Great Oz pulls levers and strings behind a velvet curtain. The painter’s expressive gesture exposed as a fiction, catalogued and coded. This is the hard road that painting has traveled. C.Wells is not American, but his work is clearly rooted in this powerful trajectory of Modern American painting that sent feeder lines north like the sprawling network of roads that pattern the Canadian landscape. Blacktop and concrete snaking seamlessly across the border inscribed with painted code.Painting often seems stuck, mired in a dead end, spinning donuts at the end of a cul-de-sac. Where to go? Think of Jim Carey as Truman gone berserk racing around a traffic circle, all lanes blocked. But then, having run backwards, he finds the bridge, then the highway, the long straight open road. I realize that in the movie, Truman’s car trip does not end in freedom (that comes later via sailboat). But let’s pretend it does because the car, hurtling out of town (the actual planned community of Seaside — Andres Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk’s flagship of New Urbanism), just works so much better here.I am convinced C.Wells is making paintings. With regard to the dilemma I mentioned earlier, clearly there is a code underlying his work: the painted road marker. And in terms of the artist’s intent, this work is clearly sincere. These are paintings. The road marker is not a system referenced to undermine painting, but one that provides a meaningful framework to continue painting within set parameters. C.Wells believes in painting with all its conditions and limitations. He has found a system that has allowed him to pull out of the monotonous endgame, while at the same time acknowledging the trajectory that led to that very predicament. He has reached back, as many artists have done, to the roots of this predicament in the work of Marcel Duchamp and the act of drawing the utilitarian into the framework of art. Herein lies the beauty of C.Wells’ work, what he has drawn from the utilitarian is an act of painting.

l917 and l911. Two gestures. Each appears to borrow from the other’s world, the artist from the utilitarian, the purposeful from the aesthetic. In l917, Marcel Duchamp plucked the urinal from the hardware store and called it “The Fountain”, giving the object a new meaning in its new context. Same object, different rules. In l911, E.H. Hines (Road Commissioner for the State of Michigan) took the paintbrush and marked the road, the broad gesture of the painter on a flat, horizontal plane, a gesture done in America, for the automobile. So much would be done in America for the automobile in the 20th century. And so much would be done with paint, on a flat horizontal surface in America as well.

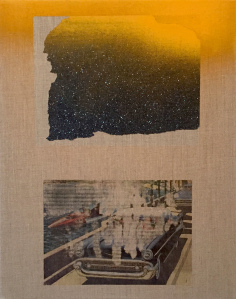

The automobile has defined the landscape and the built environment of North America. This is no revelation, it is just plain and obvious today, a given. The suburbs, the Miracle Mile (that string of cheap commercial development along the highway heading into cities and towns), flat stretched out architecture that functions as both building and billboard, the super highway that carries you around cities and bypasses towns left derelict, fast-food restaurants, the drive-thru and the three-car garage. The automobile, so the theory goes, killed the downtown, the old world, the pedestrian world. In supplanting this pedestrian world, the automobile also assumed the role of philosophical vehicle, the vehicle of wandering, contemplation and social interaction that walking once held for writers like Jane Austen, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau -out in the landscape, moving slowly through a space of quiet contemplation, like the plein air painter. It is Hines’ painted code that quides you through the driven landscape, just as painting once defined the pastoral, highly crafted English landscapes of Capability Brown and the urban parks of Frederick Law Olmsted. C.Wells’ work PLEINAIRISME points to these exchanges between painting and landscape.

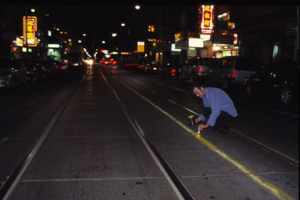

In PLEINAIRISME, we are shown the complete cycle, the original (line on the road), the act (artist in the garden painting) and the painting itself (the artifact). The photographic image is peculiar, more than just a straight record of the act of painting. Hines’ single white line on the road if framed and isolated by foliage, landscape and architecture. Then there is the painted canvas positioned exactly five inches (the width of Hines’ line) to the right of the photograph. The white line that splits the raw canvas is, as always in C.Wells’ work, actual size and painted in line marker paint making the painter’s gesture an exact copy of the line on the road. 1:1. In the photograph, the canvas is laid flat. This is the orientation of production of all C.Wells’ paintings, whether on canvas or on site, echoing not only the orientation of Hines’ gesture, but also the orien- tation of American painting (think Pollock) and utilitarian painting (think refinishing a door). PLEINAIRISME encapsulates the layered vocabulary of painting that C.Wells is immersed in: a vocabulary that includes painted gestures and codes beyond the specifics of the art gallery and studio. In working within this expanded field of painting C.Wells is well within a trajectory of art-making that, again, goes back to Duchamps, and can be traced through Pollock and Robert Rauschenberg’s use of commercially produced industrial paints. More specifically C.Wells’ current work can be connected with Lawrence Weiner’s STATEMENTS of l968, 3 works line AN AMOUNT OF PAINT POURED DIRECTLY ON THE FLOOR AND ALLOWED TO DRY, again paint on a horizontal surface. Weiner’s works would gradually expand in scale, taking in vast landscapes, their implied scale occupying entire continents, like Hines’ code.

The great Argentinean writer Jorge Luis Borges once wrote, in a poem called The Museum, 4 of a society of geographers who were so obsessed with precision that they produced a map of the world at a scale of 1:1, a map that literally covered the world it represented. Borges said that if you wandered out into the desert you could still find fragments of this tattered map. The network of roads that criss-cross and wind through the world is like Borges’ map, as are the land- scapes and architecture they form. There are, out there, many abandoned fragments and tattered remnants of past maps, past codes of ordering and understanding the world. There are many roads to nowhere; former highways become forgotten side roads, bypassed by the super highway. Route 66 is probably the most famous, now an incomplete path of 1950s America. In PLEINAIRISME, the artist’s space of action is also such a remnant, a very controlled lawn and garden, picturesque traces of Capability Brown downtown, hidden in back of a stark white modern apartment block.

The World Fairs did much to propagate a modern vision of the world, a new world of super highways, uniform architecture, systemized production, processed foods, cleanliness, hygiene, order, quality through sameness and predictability. The New York World’s Fair of 1939 was the pinnacle of this promotion of a new modern America with Ford and General Motors staging the most elaborate visionary spectacles with the automobile, obviously, at centre stage. This was the place where inventions like Hines’ system would be promoted and marketed since the core of the World’s Fair message was urban planning. It is commonly accepted today that cinema was the dominant art form of the 20th century. I would argue that it shares this honour with urban planning. Modern urban space is an automotive space, a space where the pedestrian is at risk and eyed with suspicion. Pedestrians occupy the unused space, the border of fringe terrain, moving through a space not intended for them and drawing attention to their alien ness. At heart, the painter is more pedestrian than driver.

In PLEINAIRISME, the artist is viewed (spied on?) from a balcony above, giving the image a slightly sinister slant. Who is watching/observing the painter? It is a scene reminiscent of moments in Peter Greenway’s The Draughtsman’s Contract and the narrative structure of Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window In Greenaway’s film, the artist (the observer observed). Like C.Wells in the back garden, produces views of the highly cultivated and planned landscape (a landscape that really is by Capability Brown). In Rear Window, we watch ( and watch with) the watcher. In both cases there is the suggestion that there is something not quite right about the act of observing and in both cases the central character is an artist, isolated, viewing the world through a window, which mimics a more powerful code. The Draughtsman’s window is the framing device he looks though to grid the landscape; the code it mimics is the complex social order of which he will become a victim. Jimmy Stewart’s window is the lens of his camera combined with the grid of apartment block windows. In his case, the code is ideas of community and neighbourhood, the detachment and alienation nurtured by the modern urban environment. Like Stewart and the Draughtsman, C.Wells ventured out to find the source of this vast map. Through extensive research, a constant in his work, he located and then traveled to the site of Hines’ first line – Trenton, Michigan – where he identified and repainted/restored the precise section where the code began, once more positioning himself in a 1:1 relationship with his source. This move on C.Wells’ part is important for another reason. It is evidence of being in the world, creating a body of work that is not detached and simply theoretical, but, is linked to specific places and sites, histories, communities and individuals.

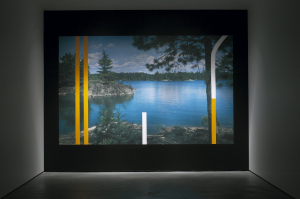

To escape the confines of the urban, you head for the wilderness, a modern phenomenon made possible again, in North America, by the automobile. Inexpensive cars, the result of Henry Ford’s application of Taylorism’s modern systematized production, made wilderness leisure accessible to the masses, made tourism boom, and spawned such automotive architecture as the motel, Holiday Inn being the classic example. In Ontario going north became the dominant tourism destination, a north that was (and is) depicted as all natural, “virgin.” To the tourist, the wilderness is always presented as the antitheses if the urban environment, an unordered and unaltered space of rest and rejuvenation, a slower space, the space, again, of Austin, Emerson, and Thoreau. But is it? Was it? For over a century the north, Ontario’s near north of tourism, has been a gridded terrain of industry, of mining, logging and settlement. Algonquin Park, Ontario’s quintessential “virgin” wilderness, is largely recent growth, the park having been widely clear-cut at the end of the l9th century, a space still actively logged. To drive across the park from Huntsville to Whitney on Highway 60 is to take a journey across a terrain of significant social and industrial history. But that won’t sell postcards; the image of pure nature does, and this image is the code laid over that terrain.

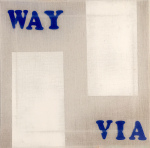

In parcel the journey with the destination, C.Wells layers two powerful codes. He maps a journey via Hines, from highway to town to countryside, the vertical lines scripting a very modern dialogue of urban to rural to wilderness. A classic northern woods, echoing the compositions of Tom Thompson and the Group of Seven, is the destination. Here, again, C.Wells has pulled from the everyday. The photomural is not his creation, but is rather a purchased, commercially produced section of wallpaper. The work is cinematic in scale and reminiscent of the project backdrops of film. Significantly, it mimics, the projected rear window of the filmed interior of the moving car, the classis projection that never seemed to be quite right, the driver’s hands wiggling the wheel out of sync with the movement of the passing landscape. In the hand loves that which is hard: the #1, virtual, the latest work in C.Wells’ ongoing performance/restoration/documentation project, the image of the artist repainting a line on the Trans Canada Highway(the #1) is matched to a changing sequence of postcard scenes representing each province. Here again, I am drawn to the projected backdrops of film and then to the background repetition of cheap cartoons (the same rock passing in the background for example), traces of Ford’s assembly line produc- tion in film. Once you notice this, it can be hard to follow the narrative. How to tell interesting stories, to be genuine, once the underlying code is exposed? This dilemma informs much of C.Wells’ activity. He overcomes this dilemma by acknow- ledging the limitations and restrictions of a code and recognizing the potential for developing meaning through rigidly set parameters. This is obvious in his ongoing engagement with Hines’ system. It is also elegantly articulated in his text works, his rotating signs with their narratives given structure and cadence by the mechanics of the presentation (three layers, rotating, requiring memory to retain and carry the narrative) and his erasure pieces (not exhibited in the exhibition) where he works through an existing text and creates verse through the erasure of words, finding another narrative buried beneath the first.5 C.Wells is here, happily, walking the terrain of John Cage who found beauty in defined systems and applied chance.

C.Wells works, for now. in an unused skating rink hidden inside a monumental failure of urban planning, a downtown mall, largely vacant, the victim of the aut- mobile and suburban malls that are now in turn falling victim to the minivan and super box stores. Since the construction of this failed mall obliterated the past beneath it, there is no history now to draw on, to revive the terrain of its footprint. A once bold visionary statement now reads like arrogant folly. This is the danger imbedded in the scale of modern urban planning with its benchmark in Haussmann’s Paris. There is no dialogue with the past here, no sense of place. This was largely the danger of much of Modernism: each new move made to obliterate its predecessor, and this includes painting. The obvious, easy response to this is to whole -heartedly reject the forms of Modernism and to create – as the movie Truman demonstrated with the New Urbanist town of Seaside – an idealized mythical past that never existed, like the “virgin” wilderness of parcel the journey with the destination. The alter- native is to look for bridges from one code to another, to find meaning in the fragments of the maps Borges spoke of. Like many of us, C.Wells occupies and moves through the fragments of modernism. He is committed to one particular fragment, a system that he lovingly restores, finding specific meaning, local significance, in each stretch of painted road.

E.N.Hines may be the most significant overlooked modern painter in North America, at least I’m going to follow C.Wells’ lead and suggest this. His canvas lay flat decades before Pollock. His scale and the continuous nature of his work (lines continue to be painted on roads everywhere) is beyond anything earth artists like Robert Smithson and Walter DeMaria could dream of. Hines’ painting, completed by others, is a monu- mental, ongoing execution of Lawrence Weiner’s early processed based works that insisted that the receiver of the idea complete the work of art. I cannot look at the lines on the road anymore without being constantly aware that I am driving through a painting. This is what good art does: it changes your perception of the world. Thank you C.Wells.

1 Yve-Alain Bois, Painting as model, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, l990

2 See Buchloh and Richter interview in Gerhard Richter, Paintings, Museum of Contemporary Art (Chicago) and Art Gallery of Ontario,1988.`Buchloh argues that Richter’s work is a cynical exercise that exposes painting as a vocabulary of signs manipulated by the painter.

3 Exhibition and book work, Seth Seigelaub Gallery, New York, l968

4 Jorge Luis Borges, Dreamtigers, University of Texas, First English Edition, l966

5 C.Wells is currently applying this strategy to sections of the Line Marking section of the Michigan Transportation Manual.